Today race and racial relationships seem in my personal opinion to be blwon way out of proportion. Technically I account for two minority groups and I have never felt that I was one because, everywhere I go I see other black people and I see other women, thus why feel outnumbered. Yet in still I do not ignore the fact that our currrent society is arranged in a way that best suits the majority first and almost every other minortiy group except African Americans. Americans as a race of people are naturally lazy and are used to the mircrowave effect and want things to happen for them qucik fast and in a hurry. I for one have been victim of these notions, but never have I fell to the assumption that I am owed anything because of my race or my gender. I have no hold no bbeliefs for racial superiority, however I do think that tend to have more privileges and opportunities that other, but the just reflects on the social captital policy. Its also so apparent that some just tend to have more amiable qualities, or have been able to manipulate the system to better benefit them (George W. Bush), while others have not. The thing with the African American community is that several of them grow to believe as their elders did that the “white man” will never allow them to make anything of themselves because of their past racial relationships, thus they figure why bother striving for greatness. The general concept of the white man keeping the black man down and yet you see so many people of color accomplishing major milestones in today’s society. Another reason why African Americans have been the least successful at manipulating society is due to the fact that some feel as if the government owes them for the sufferings of their ancestors, the depend to heavily on government assistance rather than using it to further themselves and consider it the very least that “white people” can do. I am unaware of the mindsets of other minority groups and only have insight into this one through experience. Even I at one time felt that I could only go sop far and only have a specifc type of job when I grew up, and it would be the type of jobs that I seen black women have on Tv (cooks, hairstylist, secretaries,teachers,coaches and etc). Eventually one has to let go of all other preconcieved notion about themselves, their race, their potential and abilities to motivate themselves to do whatever they want to do or become whom ever they want to be. Despite any level of discrimination that minorities have been forced to endure or the sentiment of race superiority implied by the media, it is the responisiblity of society as a whole to recoginize that we are all American and its our differences that make us that way.

Reflections

05 Dec 2010 Comments Off on Reflections

in Discrimination, Eugenics in current Society, Race & Music studies, Racial Media Exposure, Stereotypes & Racial Profiling

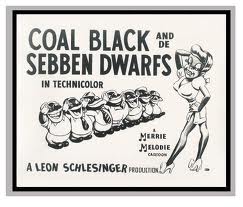

Popular Art and Racism: Embeding Racial Stereotype in the American Mindset

05 Dec 2010 Comments Off on Popular Art and Racism: Embeding Racial Stereotype in the American Mindset

in Race & Music studies, Racial Constructions, Racial Media Exposure, Stereotypes & Racial Profiling, Uncategorized

Jim Crow and Popular Culture Aritcle

Ronald L. F. Davis, Ph. D.

The onset of Jim Crow laws and customs rested upon the racist characterization of black people as culturally, personally, and biologically inferior. This image functioned as the racial bedrock of American popular culture after 1900, especially manifested in minstrel shows, the vaudeville theatre, songs and music, film and radio, and commercial advertising. So pervasive was the racial demeaning of black people, and so accepted was it by white Americans throughout the nation, that blackness became synonymous with silliness, deprivation, and ignorance. Most white Americans believed that all Africans and their descendants were racially inferior to whites, and that their common inferiority tied them together wherever they might live in the modern world.

In America, black people were portrayed as inferior almost from the time of their enslavement in the colonies in the 1620s. This racial characterization enabled white masters to justify slavery as something positive. Using racial stereotypes to justify the enslavement of blacks was especially pronounced after 1830 as white Southerners defended slavery against attacks by northern abolitionists.

This historic view of blacks became deeply embedded in American popular culture with the emergence of the minstrel show in the 1840s. By 1900, the image of silly and exaggerated black men and women in comic routines was the mainstay of musical acts, songs, and skits that dominated the theatrical scene in America well into the twentieth century. (For further discussion of the relationship of Jim Crow and minstrel shows, see Creating Jim Crow, In-Depth Essay.

The image of black people in the white mind focused on outrageous depictions of individual blacks and their assumed cultural practices. Countless representations of impoverished blacks with ink-black skin, large thick red lips, and bulging eyeballs appeared almost everywhere in the public arena. Dozens of graphic artists and illustrators prospered as racial commercial artists by drawing such images to sell products and to illustrate show bills and magazines. Most prominent was Edward W. Kemble, whose racist illustrations were notorious in America and Europe, including his 1896 “classic,” Kemble’s Coons.

Perhaps, the most popular of all the Jim Crow industries by 1900 was the sheet music field, which made the derogatory word “coon” a part of everyday language. The black American Vaudeville performer and composer, Ernest Hogan, did more than anyone else, ironically, to popularize the so-called “coon” craze and racist characterization of blacks. His wildly popular 1896 song, “All Coons Look Alike to Me,” appeared, usually illustrated with the images of ridiculously dressed black men and women, on billboards and sheet music all over the nation.

At the same time, as Jim Crow music, dance, theatre, and illustrations distorted the image of black Americans; a wave of racially driven commercial advertising flooded the landscape. Most popular were the racist trading or advertisement cards that used the outrageous images of black people to sell everything from yeast to furniture, pillows, fertilizers, hardware, cigars, breakfast food, and tobacco. Of these cards, racist advertisements that depicted a Mammy-like black woman (Aunt Jemima) selling pancakes were, perhaps, most popular. The silly “Gold Dust Twins,” who performed as half-dressed, house-cleaning pickaninnies dispensing commercial washing powder, were also especially popular. Everywhere one turned were brightly colored and skillfully drawn images of big-eyed and thick-lipped blacks eating corn, sporting fanciful attire and riding a wild pig or some other farm animal, aping white elites to comic effect, trying to ice skate, clumsily walking along a high fashion boulevard, haplessly trying to ride horses in the manner of an English gentleman, and strutting proudly in exaggerated dress at parties and “darkey” balls. And soon, the images became products themselves–racist dolls and Mammy-style metal banks flooded the consumer market as children’s toys. By 1900, so accepted was the popular concept of black inferiority that racist brand names, such as “Niggerhead,” began to appear—usually selling some aspect of blackness, such as ink or dye.

This outpouring of images, performances, and music was supported by a largely racist or else highly romanticized literary tradition. The novels and writings of Joel Chandler Harris, especially his Uncle Remus tales, written from 1888 through 1906, looked back at the days of plantation slavery as a time of racial harmony in which happy and simple-minded blacks lived with respect and dignity as slaves.

Thomas Nelson Page, whose early novels and short stories, usually narrated by elderly freedmen, portrayed, like Harris, a tranquil life in slavery where faithful blacks adored their masters and were cared for with affection and tenderness. By 1898, Page had turned bitter, however, and began depicting blacks as sinister characters that could not be trusted in freedom. No author was more racist or more popular than Thomas Dixon, whose novel, The Clansman, published in 1905, blamed all of the South’s woes on the inferior blacks who roamed the land unchecked following their emancipation.

When film and radio burst onto the American scene in the new century, the racial stereotypes were easily adapted and strengthened in these revolutionary forms of popular culture. Radio captured the imaginations of millions of passive listeners who tuned in for broadcasts of the Amos and Andy shows–the most popular radio show in America in the 1930s. Rooted in the old minstrel shows and blackfaced vaudeville acts, the program portrayed two southern black men who had moved to Chicago. Its characters of the Kingfish, a dishonest and lazy confidence man who massacred the English language by mispronouncing words, and Sapphire, his loud, abrasive, bossy, and emasculating wife, became permanent fixtures in the minds of white Americans. The program dominated radio in the 1930s and 1940s, and played as a popular television show in the 1950s.

Like radio, Hollywood films also presented blacks within the context of images from the minstrel shows and vaudeville. Usually, blacks were presented as faithful and often wise or hapless servants, resolute and devoted Mammy-type characters, and often stupid and silly chicken stealing blacks. Many of the classic film landmarks of American culture featured such stereotypical portrayals of African Americans. These films included such classics as Birth of a Nation (1915), The Jazz Singer (1927), which was the first sound film, Gone with the Wind (1939), the most popular film of all time, and the sentimental Song of the South (1946), an animated film produced by Walt Disney and based upon the Uncle Remus stories of Joel Chandler Harris.

Birth of a Nation was truly a product of its times when it hit the nation’s movie houses in 1915. It fused the two most basic racial themes of the Jim Crow South, demonstrating the close link between the two: the minstrel show and lynching. And, in the latter case, it greatly strengthened the racist image of black men as beasts who lusted after innocent white women and girls. The film, which was the blockbuster of its day, raking in over $200 million dollars from its debut in 1915 to the mid-1920s, launched a wave of “Negrophobia,” which is the fear of and/or contempt for black people and their culture. After viewing this film, many white males honestly worried about leaving their wives and children at home alone out of fear that black beasts lurked in the shadows all around. In some communities, after seeing the film, the whites randomly attacked and beat any blacks they found on the streets. The movie helped revive the long dead Ku Klux Klan and inspired a new wave of white supremacy in the 1920s.

Most “Southern Films,” although far less viciously anti-black than Birth of a Nation, played, nevertheless, to the white supremacy convictions of most Americans. Continuously voted the most popular film of all times whenever surveys are made, the epic Gone with the Wind, based on the novel by Margaret Mitchell, presented a range of black characters who exemplified various aspects of the accepted racial stereotypes. Although the black actresses Mattie McDaniel and Butterfly McQueen brilliantly played the Mammy character and the witless house servant, both women were barred from the week’s events surrounding the Atlanta premier of the film in 1939. McDaniel, who went on to be the first African American to win an Oscar for her performance as the strong and resolute Mammy, was viewed by white audiences as a loyal and faithful servant which was an acceptable black image.

And McQueen, who had starred in dozens of black theatrical performances during the Harlem Renaissance, displayed a genuine comic talent in ways that sadly supported the racist views of blacks as incompetent people. Her performance, along with those of the popular black actors Stepin Fetchet, who portrayed a lazy, whining, clown-like character in numerous films in the 1930s and 1940s, and Billy “Bo Jangles” Robinson, the tap dancing house servant in several Shirley Temple films in the 1930s, continued the long line of racial characterizations stretching from the minstrel shows through vaudeville and radio.

At the same time that black stereotypes and racist characterizations dominated the popular culture of white supremacy, significant contrasts did exist and provided refuge for black Americans. The Harlem and Chicago Renaissance movements in literature and the arts of the 1920s presented richly creative and genuine black achievements in contrast to the popular images of white supremacy.

In film, for example, over 200 “race movies” were produced between 1915 and 1945. Most of these films countered the stereotypical images of blacks, presenting them instead as doctors, lawyers, soldiers, cowboys, gangsters, and men and women of character. Most importantly, they featured all-black casts. Three Oscar Micheaux films were among the best of these: Within Our Gates (1920), which presents the lynching of Leo Frank in Atlanta; The Brute (1920), which is the story of a black man standing up to a lynch mob; and Birthright (1939), which tells of a black Ivy League man who returns to the South after college. In the white mainstream, moreover, the popular musical, Show Boat, featuring the great black actor and singer, Paul Robeson, was one of the first films to show black people as strong and complex men and women victimized by racism in America.

Still, images of blacks as lazy, thieving, conniving people; hapless or faithfully devoted servants; or dangerously sex-crazed beasts dominated the media during the Jim Crow era. The accepted racial stereotypes supported a racist America in which lynching, the Ku Klux Klan, disfranchisement, and segregation ruled the land. At a sold out charity benefit during the premier of Gone With the Wind in Atlanta in 1939, local promoters recruited blacks to sing in a “slave choir” on the steps of a white-columned plantation mansion built for the event. Among the local African Americans in the choir was a young black man dressed as a slave who made his first appearance that evening in the national spotlight. His name was Martin Luther King, Jr.

Selected Secondary Sources:

Bernardi, Daniel. ed. The Birth of Whiteness: Race and the Emergence of the U. S. Cinema. New

Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1996.

Bogle, Donald. Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies & Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films. New York, New York: Continuum, 1989.

Cripps, Thomas. Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film, 1900-1942. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1977. ______. Making Movies Black: The Hollywood Message Movie from World War II to the Civil Rights Era. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Fredrickson, George M. The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817-1914. 1971. Reprint, Hanover, New Hampshire: Wesleyan University Press, 1987.

Hale, Grace Elizabeth. Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890-1940. New York, New York: Pantheon, 1998.

Levine, Lawrence W. Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom. New York, New York. Oxford University Press, 1977.

Litwack, Leon F. Troubled In Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998.

O’Connor, John E. and Jackson, Martin A. eds. American History/American Film: Interpreting the Hollywood Image. New York, New York: Continuum, 1988.

Pieterse, Jan Nederveen. White on Black: Images of African and Blacks in Western Popular Culture. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1991.

Powell, Richard J. Black Art and Culture in the 20th Century. New York, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

Toll, Robert C. Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

The Sound of Silence: Talking Race in Music Education

05 Dec 2010 Comments Off on The Sound of Silence: Talking Race in Music Education

in Race & Music studies, Race Relations, Racial Constructions

Deborah Bradley

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Raciology: the lore that brings the virtual realities of “race” to dismal and destructive life

Gilroy 2000 (p. 11)

Introduction: Social Justice or Colonialism

Although general education has focused attention in this direction for some time, it seems that the concept of social justice may finally have become a topic of widespread interest within music education, signaled by the International Conference on Music Education, Equity, and Social Justice held in October 2006 at Teacher’s College, Columbia University in New York City. I say “finally” because the concerns are not new. Issues of social justice have lurked in the academic margins of music education for quite some time. Nearly two decades have passed since Roberta Lamb and Julia Koza brought feminist critiques of music education philosophy and practice into its discourse. The concerns they raised about gender bias in choral (Koza 1993a, 1993b), instrumental and general music education settings (Koza 1992; Lamb 1994a; Lamb 1987) and feminist critiques of music education philosophy (Gould 1994; Koza 1994a, 1994b; Lamb 1994b; Lamb 1996; Morton 1994) motivated me to think more deeply about what it means to teach music. The issues raised in their work, as well as an increasing understanding of music’s sociality (Bowman 1994a, 1994b) piqued the curiosity that eventually became my scholarly focus on issues of multiculturalism and racial politics. The reasons for my turn toward anti-racism as a discursive lens for analysis will be addressed later in this paper, but my use of this lens is by no means a rejection of feminist ideals. I continue to find inspiration in the work of scholars whose analytic views might be characterized as “feminist” (Gould 2005; Jorgensen 1996, 2003; Koza 2001, 2003; O’Toole 1994, 2005) and whose writings address the ways music education reproduces unequal power relations through practices that are often exclusionary.

Although concerns about issues of power and hegemony have been explored vigorously, both in print and at conferences in recent years (at MayDay Colloquia, in this Bradley, D. (2007) “The sounds of silence: Talking race in music education” Action, Criticism, and Theory for journal, and elsewhere), little seems to have changed in the way music is taught in schools and other settings. Where changes have occurred, they have been largely isolated and associated with individual initiatives. The Teacher’s College conference themes of social justice and equity in music education suggest, then, that the discipline may be willing to reflect upon itself more intently and critically. While I take heart that music educators are beginning to give social justice the serious consideration it deserves and to discuss ways of integrating social justice theory more effectively into teaching praxis, I am also concerned that despite the best of intentions many of us have not considered adequately what social justice means and entails. I worry that social justice may become simply a “topic du jour” in music education, a phrase easily cited and repeated without careful examination of the assumptions and actions it implicates. That can lead to serious misunderstandings. Social justice may, for instance, be misconstrued as an act of charity: classes study and perform music from another culture, viewed through a lens that suggests the people of that culture somehow need “rescuing,” and resulting in a perceived need to “do something” that leads in turn to the donation of concert proceeds to some related cause.

Charitable organizations do good work in the world, but they do not by and large create the widespread change that diminishes or eliminates the need for their existence. (If societies were socially just, there would be little if any need for such organizations.) For this reason, I suggest that the “do something” motivation among some music educators leads to what I consider acts of charity posing as social justice. While the educational process that leads to such motivation may raise student and audience awareness of social justice issues, the status quo remains intact, and the participants often come away feeling self-satisfied, even pleased about their sense of social responsibility. In best-case scenarios, such experiences may eventually lead to greater self-reflexivity on the issues. But what if the experience is an endpoint rather than a beginning? In a recent article entitled Stealing the Pain of Others, Razack(2007) argues that movies like Hotel Rwanda often make (white) audiences feel good about themselves through an affirmation of individual and national capacities for compassion associated with a sense of moral superiority. I believe the same argument might be made about many musical performances directed towards charitable fund-raising: They often leave students, teachers, and audiences feeling good by affirming individual and collective capacities for compassion. But these capacities and feelings often stem from, and reinforce, an unacknowledged and deeply problematic sense of moral superiority.

Presumed moral superiority served to justify colonial conquests and their related brutalities. To view other cultures or people through the lens of moral superiority reiterates these colonialist power relations within North American educational systems:

Colonialism, read as imposition and domination, did not end with the return of political sovereignty to colonized people or nation states. Colonialism is not dead. Indeed, colonialism and re-colonizing projects today manifest themselves in variegated ways (e.g. the different ways knowledges get produced and receive validation within schools, the particular experiences of students that get counted as [in]valid and the identities that receive recognition and response from school authorities) (Dei & Kempf 2006, p. 2).

Colonialism is alive and well, I fear, within many North American music education programs. Our music education curricula continue to validate and recognize particular (white) bodies, to give passing nods to a token few “others,” and to invalidate many more through omission. The western musical canon predominates our curricula, while we continue to argue whether popular music should have a place in what our students learn, and which styles of popular music are “appropriate.” Musical practices from around the world remain marginalized as curricular add-ons, if acknowledged at all.

The results are visible when we take a serious reflexive look at who participates, and who does not, in typical school music programs. In my local area public school district, which I believe is not atypical in the U.S.A., ensembles at the elementary level are diverse, since participation in music is required for all students. At K-5 levels, the student population is approximately 51 percent white, 10 percent Asian, and 24 percent African-American. Hispanic students comprise 15 percent of all elementary level students, and Native Americans less than 1 percent. However, in middle school the demographics begin to change, and by grade twelve, 70 percent of the total high school student enrollment is white. Only 15 percent of the total population of high school students participates in any of the fine arts course offerings.1 Of this total, 64 percent are white. The picture becomes even more disturbing when other measurements are used. In grade twelve, only 13 percent of students enrolled in fine arts are from low income families, and only 4 percent of high school fine arts students are considered to be special education students, while only 1 percent of students participating in the fine arts in high school are ELL students (English language learners).2 If we look closely, we may recognize that there is much about our profession that begs examination of its possible role in perpetuating inequities, racial inequities among them.

What constitutes social justice in education?

How do we begin to make changes within music education that seek out, encourage, and validate the contributions of all people in our schools and communities and in the world at large? In doing so, how might we move beyond isolated acts of charity that pass for social justice and reiterate colonialist attitudes of moral superiority towards others? I submit that the transformation of music education as/for social justice requires intensive reflection on our individual and collective beliefs and practices. While there are a number of areas where inequities exist in music education, my remarks in this paper will focus on race and racism since this is where I most often direct my scholarly attention. Before addressing race and racism as issues of social justice specifically, though, I want to frame the discussion with two related general concepts of social justice. Since social justice is a concept that means different things to different people—there are, as Griffiths observes, a “diversity of understandings, even though some of the differences are serious, even bitter” (Griffiths 1998, p. 4)—my intention in offering these definitions is neither to foreclose debate nor to exclude other alternative possibilities. But I hope, through a brief discussion of these two definitions, to orient the reader to ways of thinking that open the space for what follows in this paper: a discussion of anti-racism, white privilege, and the difficulty many white people experience talking about race. If we can overcome the taboo about naming race in discussion, and begin to talk more knowledgeably and confidently about racial issues, we can begin to make our music education praxes more racially equitable and socially just.

To begin the discussion, I will look at Connell’s concept of social justice in education, which he describes as “taking the standpoint of the least advantaged.…[U]nderstanding the real relationships and processes that generate advantage and disadvantage is essential in evaluating the practical consequences of any action that claims to embody the interests of the least advantaged” (Connell 1989, p. 125). Connell’s definition needs to be problematized, as does any attempt to provide an overarching definition for as complex and multifacted a concept as social justice. I introduce this quotation acknowledging its inherent tensions: they are precisely those that, left unexamined, reiterate the colonial power relations that educating for social justice ought to disrupt. Who are the “least advantaged” to which Connell refers? Who decides what counts as advantage and disadvantage? These are questions of power and privilege—indeed, of white privilege—embedded within the academic discursive requirements to label and define (Ellsworth 1997), requirements considered integral to credible scholarship. I offer this broad definition of social justice primarily because of the process Connell outlines: to evaluate the practical consequences of any action that claims to embody the interests of the “least advantaged.” Such claims are precarious, and Connell’s suggestion to evaluate their practical consequences implies the need for our actions, as well as our discourse, to be self-reflexive. Taking the standpoint of the least advantaged is not a call to “speak for” or “act for” (positions that reinscribe colonialism) but a call to stand alongside: to speak with and act with in ways that require reciprocity and collaboration. This approach has its roots in anti-hierarchical traditions of thought, based upon the fact that “ordinary people do not need an intellectual vanguard to help them to speak or to tell them what to say” (C.L.R. James, cited in Gilroy 1993, p. 79).

Griffiths (1998) offers a definition of social justice similar to Connell’s: “Social justice is what is good for the common interest, where that is taken to include the good of each and also the good of all, in an acknowledgement that one depends on the other. The good depends on there being a right distribution of benefits and responsibilities” (p. 102). Here, too, the question who decides what is in the common interest may be read as problematic, since the ability to make such decisions usually resides with those who hold power—in government, in school boards, in classrooms, in academic research. Griffiths also acknowledges that reciprocity and interdependency are key concerns for social justice. As she writes in the early pages of Educational Research for Social Justice, concerns for social justice are more about processes than outcomes. Social justice is characterized by continual checks and adjustments to the situation at hand and is never static (p. 12). The reflexivity implied by the checks and adjustments is one way to mitigate power relations and allow for the “right distribution,” both of the benefits and the responsibilities that characterize socially just education.

Terms such as “least advantaged” and “common good” are indicative of the way academic discourse reproduces institutionalized whiteness, which I will address later in the paper. While such terms may be read as patriarchal or suggestive of a “god’s eye view,” it is also possible to read them as inclusive and fluid. For example, who the “least advantaged” are depends upon context. In some cases the least advantaged may be students of color in classrooms that seek to impose invisible (white) norms. In other situations girls and women may hold the least advantage, and in still others students’ sexual orientations may determine advantage. The least advantaged might be second-language learners in schools, students with learning disabilities, physical challenges, and so forth. In all situations, relative advantage and disadvantage are determined by the intersection of oppressions like race, gender, class, sexual orientation, and ability. Acknowledging the intersections of oppressions3 is crucial to anti-racism, and is one of the main reasons I utilize this perspective in my scholarly endeavors. For my work, anti-racism provides a useful way of interrogating how the “common good” is construed in educational practice.

Anti-racism as a discursive framework for social justice in music education

As a lens for analysis of oppressions within an educational agenda for social justice, antiracism provides a discursive framework4 for questioning the roles of societal institutions including school, home and family, museums, the arts, justice, and the media in reproducing inequalities of race, gender, and ability (Dei 2000, p. 34). Recently, anti-racism discourse has also engaged in interrogation of ultra-nationalism as a form of (racist) oppression (Gilroy 2004), and oppressions based upon language, or linguistic racism (Amin & Dei 2006). While sharing much terrain with other anti-oppression discourses, including feminism, anti-racism approaches the intersectionality of oppressions, maintaining the saliency of race in analysis. Anti-racism examines issues of equity (understood as the qualitative value of justice), the need for multiple voices and perspectives in the production of knowledge (representation), and the ways institutions respond to challenges of diversity and difference as the intersections of race, gender, class, sexuality, language, culture and religion (Dei 2000, p. 34).

Many North American music education programs exclude in vast numbers students who do not embody Euroamerican ideals. One way to begin making music education programs more socially just is to make them more inclusive. For that to happen, we need to develop programs that actively take the standpoint of the least advantaged, and work toward a common good that seeks to undermine hierarchies of advantage and disadvantage. And that, in turn, requires the ability to discuss race directly and meaningfully. Such discussions afford valuable opportunities to confront and evaluate the practical consequences of our actions as music educators. It is only through such conversations, Connell argues, that we come to understand “the real relationships and processes that generate advantage and disadvantage” (p. 125). Unfortunately, these are also conversations many white educators find uncomfortable and prefer to avoid.

White educators’ reluctance or inability to discuss race is, I assert, part of the very process that maintains systems of advantage and disadvantage within music education. In order to break down this system, the racially dominant need to learn, as Howard (2006) puts it, to “articulate their accountability and experiences of grappling with whiteness” (p. 59). This must go further than the detached rational discussions common to critical academic writing, which create possibilities for individuals positioned as white to find an “out.” Rather, Howard argues, each individual member of the racially dominant group must “openly grapple with his/her own implication in whiteness” (p. 59).

In grappling with my own whiteness within the context of this essay, I acknowledge both the irony and the complexity of power relations implicated by my attempts, as a white scholar, to explore race and racism in ways that go beyond “detached rational discussion.” I am well aware that writing about whiteness will not undo my white privilege—indeed, in many respects it serves to uphold it. As Thompson (2003) suggests, writing about whiteness redounds to whites’ benefit institutionally, politically and morally, in that whites get “credit” for such work. “Perhaps in a few years,” she writes, “we will know better how to talk about whiteness in academia without reinscribing all the instrumentalities of academic whiteness, but for the moment, we are still building the tools we need to build antiracist tools” (p. 9). The effort to bring the topic of race into music education will, I hope, be viewed as one such tool. I make this effort not as a way to reinforce my own white privilege (although it inevitably does), but as a means to “probe the silences around various racisms” (Dei 2006, p.15). Dei states,

The most important question today is not who can do critical race work or antiracist work, but rather, whether we are all prepared to assume the risk of doing so. Not everyone who speaks about race is heard. In fact, racial minority bodies speak race all the time but are heard differently. . . . In order for certain issues about the experiences of racism to be accepted in public consciousness, they must be raised by a dominant body (p. 15, italics in original).

As stated previously, one goal for this essay is to articulate some of the reasons we who identify as racially white find discussions involving the naming of race difficult to engage in, even when all the participants in the conversation are committed to issues of social justice. My intent is to interrogate whiteness within music education, including my own implications in white privilege. In what follows, I will look at two related issues: the socialization that makes conversational “race talk” unacceptable in “polite company”, and the institutionalization of whiteness that influences what we are able to say and write in academic settings. If we can understand, through theory, that the taboo surrounding race talk is part of a process of maintaining advantage in a white supremacist system, perhaps we may ultimately find the courage to talk openly, and begin to dismantle the system that disadvantages so many.

By targeting “race” specifically, there is a risk that my words may seem to ignore or erase other oppressions. I believe that is a risk worth taking, however, since there is danger in failing to acknowledge the specificity of the oppression (Moraga & Anzaldúa 1981, p. 32), and because race is a “social construct with powerful social and political implications that has been muted . . . or pitted against other subjectivities—particularly class and gender—to render it ‘undiscussable’ as a difference or a site of struggle” (Ladson-Billings 1996, p. 249). My intent is not to occlude other forms of oppression; neither is it to place them in opposition to concerns for racial equity. Rather, my goal is to bring “race” into relief within the variety of discussions and approaches that a socially just music education might entail.

If, as Ladson-Billings (1996), Gilroy (2000), Williams (1997), Dei (2000), and other scholars assert, race is socially constructed, it does not “really” exist in a biological sense. Why, then, are we so reluctant to talk about it—to introduce serious discussions of race and racial issues into music education? My hope here is that by analyzing that reluctance, we may begin to move music education’s newfound concern for social justice beyond its current, naïve state—a state in which we persist in using “language that ignores its own partiality, that refuses to engage the ideological assumptions that underlie its vision of the future, and that appears unable to understand its own complicity with those social relations that subjugate, infantilize, and corrupt” (Giroux & Simon 1989, p. viii).

Many, or perhaps most, current music education practices in North America make little or no attempt to take the standpoint of those least advantaged. In fact, programs based on the western canon are constructed on precisely the opposite premise: the standpoint of those with the greatest advantage. In the great majority of cases, music teachers and students are white and affluent. To name race in discussions of music education not only invokes discomfort, then, it raises tacit fears that if we de-center the western canon in music education to acknowledge and engage in forms of music making that are more culturally relevant to our students, our race-based positions of advantage may be compromised. As Gilroy (1993) has argued, “the recent history of black musics which, produced out of the racial slavery which made modern western civilization possible, now dominate its popular cultures” (p. 80).5 Might the collective reluctance of North American music educators to embrace popular and world musics express an unconscious fear of losing the white privilege represented by canonic knowledge and expertise?

Avoiding the “R Word”

Talking about race can be risky business. As Morrison (1992) notes, avoiding the mention of race in conversation is often considered a graceful, liberal gesture (p. 10), yet it is at the same time a gesture that discredits difference. Attempts to focus deliberately on issues related to race as a named concept go against whites’ socialization. Researchers have noted that among white students in anti-racism classrooms, naming race in conversation often results in wandering “off topic”6 as a means of avoiding discomfort. Such avoidance behavior has been identified as “a diversion strategy”:

We have found that White students frequently use diversion strategies when discussing race. We have seen White female students divert the conversation to a discussion of feminist issues, White gay and lesbian students equate racism with homophobia, and students with body types that do not fit the cultural norm turn their attention to weight issues (Rich & Cargile 2004, p. 360).

Granted, this tendency may help white students develop empathy with the victims of racism as well as gain some insight into the way various oppressions intersect with race. But at the same time, as Rich and Cargile argue, it reveals the discomfort many whites experience when race is the specific focus of discussion. I too have witnessed similar diversion strategies among music educators, including some that are uniquely “musical.” One such discussion in which I took part (at a MayDay Group colloquium) began by exploring the ways race may be embedded as code within the idea of multicultural music education but soon became diverted to, among other things, a discussion of the future (sustainability) of marching bands. While the discussion of marching bands implicated concepts of whiteness, no one named the concept or addressed race specifically. When I pointed out these diversions during subsequent discussion, one person commented that she “did not know how to talk about race.” Her statement met with affirmative head nods, indicating to me that others in the room shared similar concerns. This is a common phenomenon. In Colormute, an ethnography focusing on “race talk” in a California school system, Pollock (2004) states:

[A]ll of the educators I talked to—teachers, teachers in training, school coaches, principals-to-be, superintendents—requested that I provide a more specific guide to how to talk racially in school settings. They argued that they themselves ‘lacked the language’ to talk successfully about race, as racial language was itself loaded, difficult, incredibly hard to make ‘positive.’ One superintendent said succinctly that she felt ‘handicapped by language’ that was always ‘woefully inadequate’ (p. 220, italics in original).

This “handicap by language” is not surprising given that, “in matters of race, silence and evasion have historically ruled . . . discourse. Evasion has fostered another, substitute language in which the issues are encoded, foreclosing open debate” (Morrison 1992, p. 9). One of the “substitute languages” for race about which I have written is the one known as multiculturalism (Bradley 2006b), a language that comes into play within music education whenever we encounter musics that lie outside the Western art tradition. This act of sorting into musical bins labeled “western” and “other” implies a “multicultural unity . . . promulgating a generic or homogenizing term which would cover all non-white others” (Bannerji 2000, p. 29). It is also, I suggest, one of the things that makes specifically naming race difficult in multicultural discourses.

Although in the United States it is common to use the term multiculturalism to refer to both liberal forms of multiculturalism and to describe critical multicultural pedagogies, in Canada, Great Britain, Australia, and other areas, anti-racism refers to those enactments of multiculturalism grounded in critical theory and pedagogy. The term anti-racism makes a greater distinction, in my opinion, between the liberal and critical paradigms of multiculturalism, and is one of the reasons I find the anti-racism literature useful for analyzing multiculturalism in music education. The primary differences between (liberal) multiculturalism and anti-racism are described by Dei (2000):

[M]ulticulturalism works with the notion of our basic humanness and downplays inequities of difference by accentuating shared commonalities. . . . Anti-racism shifts the talk away from tolerance of diversity to the pointed notion of difference and power. It sees race and racism as central to how we claim, occupy and defend spaces. The task of anti-racism is to identify, challenge and change the values, structures and behaviors that perpetuate systemic racism and other forms of societal oppressions (p. 21).

While I believe that as educators, we have an obligation to teach in ways that encourage change within individuals’ thoughts and actions, multiculturalism’s discourse of shared commonalities allows for easy slippage away from naming race in discussions of difference, relying instead upon the language of “culture,” “ethnicity,” “nationality,” or the peculiarly Canadian language of “visible minorities” (Bannerji 2000)—a term specifically denounced by the United Nations in March 2007 as racist. Yet “it is clear to most anti-racist educators that racialized minorities experiencing a deracialized approach to schooling feel the material consequences of race profoundly” (Dei 2000, p. 20). Race is a fiction that masquerades as reality with great success. Hence, my interest in anti-racism education seeks to maintain race and racial issues as a salient focus, and insists that talk about race be explicit, not covert or implied. However, in making race explicit in our conversations, it is crucial to recognize and avoid “the power of race talk that resides in the making and experiencing of the ‘Other’ and the creation of Othered subjects” (Dei & Kempf 2006, p. 9). Racism is not just about skin color; it is about how we use power to engage issues of language, sexual orientation, class, gender, ability, religious and ethnic oppressions (p. 17).

Breaking the silence: Why it is important to talk about race

If white educators lack the language to discuss adequately a concept that is often dismissed as a “fantastic fiction,” why should we worry? The idea that we do not talk about race is itself a “fantastic fiction”—the use of coded language and euphemisms such as “poverty problem,” “welfare,” “crime problem,” “urban schools,” and even “diversity” and “multiculturalism” routinely find their way into everyday speech, including the public speech of teachers. These codes are “a back-handed way of talking about what we believe is a ‘race problem’ ” (Landsman 2001, p. xi), a “problem” that in large part has been linked directly to presumed failures of public education. We know the alarming statistics, and although estimates vary among the many studies related to minority student achievement, one common denominator is the wide disparity in graduation rates from high school of white and minority students, particularly in the United States and Canada. In an American study based on the class of 2002, about 78% of white students graduated from high school with a regular diploma, compared to 56% of African-American students and 52% of Hispanic students (Greene & Winters 2005, p. 1). Of the students who completed high school in 2002, “only 23 percent of African-American students and 20 percent of Hispanic students left school ‘college-ready,’ compared with 40 percent of white students” (p. 1).

The demographics of schools in North America are changing quickly. By some estimates, 40 percent of students in the United States are of color (Landsman 2001, p. ix). Yet as the number of students of color increases, the percentage of teachers of color is shrinking. At present, teachers of color make up only about 10 percent (p. x) of the total number of teachers. With statistics suggesting that only just more than half of African-American and Hispanic students who enter high school actually graduate, the magnitude of the issue is readily apparent. Public education is a racialized endeavor that gives advantage to white students, despite so-called multicultural efforts to make the curriculum more diverse and culturally relevant to changing student populations.

If we believe that our responsibility as music educators is to do more than provide musical training (Bowman 2002), and that a critical pedagogy is crucial to education (as differentiated from training), then it follows that race and racial inequality must become issues to which we music educators speak directly, rather than through code. DeNora (2000) posits music “as taking the lead in the world-clarification, world-building process of meaning making” (p. 44); it is, she asserts, “a resource to which actors can be seen to turn for the project of constituting the self, and for the emotional, memory, and biographical work that such a project entails” (p. 45). If DeNora is correct in these assertions, then these acts of meaning making can surely be deployed in ways that bring the racialized system of white advantage into clearer focus. Once this picture becomes clear, it is increasingly difficult to ignore the raciology—“the lore that brings the virtual realities of ‘race’ to dismal and destructive life” (Gilroy 2000, p. 11)—at work within music education. Practices that ignore musical traditions outside of the western canon, or that incorporate a few select traditions merely as exotic add-ons, perpetuate raciology and racism.

Taking the risk of talking about race is important both for the future of music education as a discipline, and for our students who look to us for guidance on their journeys to becoming music educators. Until we are able to break the silence that maintains music education’s complicity in perpetuating racism by leaving whiteness the undisturbed and undisputed cultural norm, our concerns about social justice in music education will amount to little more than lip service.

Discredited Difference, Implicit Associations

The incorporation of race into music education discourse in recent decades has often taken the form of a standardized “laundry list” that is appended to the ends of sentences: for example, the assertion that “we must remain conscious of all forms of oppression including those based upon gender, race, ability, etc.” While this is an advance from writing that ignores sites of oppression altogether, the laundry list does little to help us think about how racialized concepts of music are embedded in our actions as music educators. This may be a direct result of the way white people are socialized to avoid discussion of race overtly. As I mentioned earlier, we have developed coded language to evade talk about race in polite company. When those codes are put aside in favor of direct talk, Morrison (1992) observes, “tremors” break out, a situation “further complicated by the fact that the habit of ignoring race is understood to be a graceful, even generous, liberal gesture. To notice is to recognize an already discredited difference” (pp. 9–10).

Morrison’s last sentence is telling. Why are differences based upon skin color considered discrediting and thus an unfit topic for discussion in polite company?7 Why do we avoid confronting issues of race directly, instead opting for a discursive dance of conversational code words? Landsman (2001) offers the following explanation:

Many of us, in many walks of life, are nervous talking about race. We are so often afraid we will say the wrong thing, and so we say nothing. We become quiet, defensive, ashamed, or unwilling to respond. We pretend the racial differences do not exist; we are all alike under the skin, aren’t we? Thus, we do not acknowledge the experiences of people of color, precisely because of their skin—black, brown, yellow, or white, dark or light (p. xi, italics in original).

The fear of “saying the wrong thing” is for many people actually a fear of being labeled “racist” for speaking openly about race. “One anthropologist has described the ‘fear of being labeled a racist’ as ‘perhaps one of the most effective behavioral and verbal restraints in the United States today’ ” (Van Den Berghe, cited in Pollock 2004, p. 2). Yet the ongoing discursive dance around the “r word” sometimes creates strange situations that illustrate how our avoidance of race talk perpetuates racism within education. Patricia Williams (1997) tells the story of her son, who had been labeled “color-blind” by three different teachers in his nursery school. She took her son to an ophthalmologist for testing, only to be told his ability to discern color was “normal” for a child of his age. Her investigations into this misunderstanding brought out the paradox of “color-blind” attitudes towards race. Her son had decided that naming colors was unimportant—in fact, he adamantly refused to name colors—because he had heard repeatedly in school that “it doesn’t matter if you are black or white or red or green or blue.” Yet the very reason his teachers had begun reciting this colorblind litany was in response to a playground scenario in which children had been fighting over whether or not black people could play the “good guys” (p. 3). While the child’s misunderstanding makes an amusing anecdote, it is a story that suggests how raciology finds its way into educational settings even for children in nursery school. Williams’ son’s literal (and quite age-appropriate) interpretation of his nursery school teachers’ litanies resulted in his acquisition of a deficit label. Had she not intervened in this case, her son might have been set on the path to join “the disproportionate numbers of black children who end up in special education or who are written off as failures” (p. 5). The over-representation of students of color among those who have been identified as learning-disabled is among the concerns that lead to minority students’ disengagements from school (Dei, James, James-Wilson, Karumanchery, & Zine 2000, p. 9). I wonder if the same behavior exhibited by a white three-year old might result in that child being labeled as color-blind. I suspect that a white child refusing to name colors in response to the “it doesn’t matter” mantra would be cited as evidence of the absence of racism in the nursery school, rather than an acknowledgement of its presence.

When university students or participants in anti-racism workshops claim that racism no longer exists or that it has no material impact on their lives, hooks (2003) conducts a simple exercise. She asks the class to write down on a piece of paper their response to a hypothetical scenario: if they were to die and come back to life, what identity would they choose: white male, white female, black female, or black male? “Each time I do this exercise, most individuals, irrespective of gender or race invariably choose whiteness, and most often white maleness. Black females are the least chosen” (p. 26). hooks then asks students what prompts their choices. She explains that most offer a “sophisticated analysis of privilege based on race (with perspectives that take gender and class into consideration).” She describes this disconnect between the “conscious repudiation of race as a marker and their unconscious understanding” as a gap that must be bridged before meaningful discussions of race and racism can take place. hooks describes this exercise as a way to help students move past denial of racism’s existence and to begin their work towards more unbiased approaches to knowledge (p. 26).

The gap between conscious repudiation and unconscious understandings of race, even when recognized, may be difficult to bridge. Gladwell (2005) discusses the disconcerting results of the Implicit Association Test or IAT8 for racial prejudice. The test operates on word and image associations. Images of white people are paired with the word “good” or other positive attributes; images of black people are paired with words suggesting “bad” or negative attributes in what is termed the stereotype congruent test. Response times for the various paired words are calculated. Then the test is reversed (stereotype non-congruent test): formerly positive images are paired with negative attributes and vice-versa. Because researchers realized the order in which tests were administered affects results in some cases, they controlled for item order.

In the majority of tests taken by white participants, the response times for the stereotype non-congruent test increase significantly, suggesting that many white people, even those who do not consider themselves to be racist, have difficulty breaking associations of white with good and black with bad. Thus the association of black with “bad” unconsciously influences how we talk about race, and, may I suggest, influences opinions about “other people’s musics.” If researchers developed an Implicit Association Test based upon genres of music such as hip-hop, Afro-pop, and Bollywood—contrasted with European classical music—would response times reveal similar racially-influenced response sets?

The frequently replicated IAT results for race are discouraging in their implication that even with conscious effort, it is difficult to unlearn white supremacist thinking. hooks (2003), however, denies emphatically and equivocally that this it so. She claims,

[T]his false assumption gained momentum because there has been no collective demonstration on the part of masses of white people that they are ready to end race-based domination, especially when it comes to the everyday manifestation of White-supremacist thinking, of white power (p. 40).

It is difficult to begin the work of ending race-based domination if we cannot talk about race without discomfort, anxiety, or fear of reprisal. The silence among whites on issues of race speaks volumes. In recent years, white academics have begun to think and write about race. Many have done so in support of colleagues of color, yet this support is frequently criticized both by scholars of color and white scholars. Thinking about race and racism in some circles carries the stigma of “dirty work” best left to black folks and other people of color. Some see it as a form of “acting out” for privileged white folks (hooks 2003, p. 27).

While hooks sincerely commends white scholars and anti-racism activists who understand why they have made the choice to be anti-racist, she is concerned that white people who do anti-racism work tend to be represented as “patrons, as superior civilized beings” (p. 27). The result is that activists are “typecast, excluded, placed lower on the food chain in the existing white-supremacist system” (p. 27). The “can’t win” box created by such arguments reinforces the difficulty of breaking through the discomfort associated with discussing race, both in academic discourse and daily conversation. This “double bind of whiteness” (Ellsworth 1997) works against meaningful dialogue about race in many disciplines, including music education. Still, as Dei reminds us, the important question is not who can do anti-racist work, but whether we are all prepared to assume the risk of doing so (Amin & Dei 2006, p. 15).

Institutionalized Whiteness

While I agree with hooks that it is possible for whites who are motivated to overcome their racist socialization, I also believe that anti-racist efforts must concurrently focus on systemic change. Bland forms of multicultural education will not in and of themselves overturn institutionalized whiteness, or what hooks calls white supremacist thinking. Systemic change, however, is painfully slow and difficult. Institutions of higher education resist change by exerting pressures—sometimes tacit, sometimes overt—that suppress dissenting voices and talk about disparities based upon race. It is one of the ways that power operates within institutions. As Foucault (1978) explains in The History of Sexuality:

Power is essentially what dictates its law . . . Power prescribes an “order” . . . that operates . . . as a form of intelligibility . . . . Power acts by laying down the rule: power’s hold . . . is maintained through language, or rather through the act of discourse that creates, from the very fact that it is articulated, a rule of law (p. 83).

This concept of power as productive, as “the operation of political technologies throughout the social body”(Dreyfus & Rabinow 1983, p. 185), suggests that “whiteness, like all ‘colors,’ is being manufactured, in part, through institutional arrangements” that create and enforce racial meanings, co-producing whiteness alongside blackness and other colors in symbiotic relationship (Fine 1997, p. 58).

Fine and her colleagues conducted a study in a prominent law school from which dropouts were rare. They surveyed first, second, and third year law students’ beliefs, attitudes, and experiences. The data related to attitude revealed vast differences among first year students in political perspective, levels of alienation, and vision for the future when analyzed by both race and gender. By year three, however, the differences were barely discernible, indicating a process of “professional socialization” whereby the law students grew anesthetized to things that as first year law students they had considered outrageous (such as sexist jokes). “First-year women reported concerns with the issues of social justice and social problems, and even dismay at the use of the generic ‘he.’ By year three their political attitudes were akin to the white men’s (p. 61). This anesthetization was not without personal cost. Students’ suppression of critical dispositions manifested itself apparent in “lowered grades, worsened mental health, and conservatized politics for white women, and women and men of color” (p. 61). The climate of whiteness in the law school created self-doubt for students of color, as one black woman explained:

I don’t know, maybe I’m just paranoid or something. And I wonder how people are perceiving that . . . I get the sense that maybe people won’t listen to me as much as if I were a white person saying it. And then people, when they do listen to me, they say, ‘well of course she’s going to say that, because she’s thinking of her own self-interest’ (p. 61).

I wonder what a similar study focused on music teacher education might find. I have had conversations with music education students who told me they were discouraged by their applied music teachers from pursuing interests such as a world percussion ensemble,10 or outside activities like music theatre, so that they could devote more time and attention to Western classical music, a genre in which they were told they were “deficient.” The result of such institutional disciplining is that the very students who might seek to become proficient in more varied forms of music making, and who might subsequently bring these alternative perspectives into their classrooms, are discouraged and sometimes barred from doing so. Upon graduation from teacher education programs, they feel qualified only to teach the canon. One of my graduate students recently made the following comment in his course journal:

Curse the music school that has not prepared me in anything other than the replication of “high” “art” “music”!!! How can I be a musician and not ever have heard Paul Simon and the Graceland album! I feel angry at my narrow musical training.

The narrow focus on Western art music found in many university music programs maintains the institution’s focus on white culture. The lack of substantive change in postsecondary music programs (despite profound changes in the school population that music teacher graduates will serve) assures the reproduction of whiteness within music education. Bourdieu’s (1991) description of the “magic” effects of “institution” provide insight into one of the ways that universities produce and reproduce whiteness by discouraging change.

Despite his use of gendered language, I believe Bourdieu’s point regarding institutional disciplining speaks directly to the ways that music education students come to believe that music of the European canon is superior, and thus the most (indeed, in some cases, the only) music appropriate for educational purposes:

The act of institution is thus an act of communication, but of a particular kind: it signifies to someone what his [sic] identity is, but in a way that both expresses it to him and imposes it on him by expressing it in front of everyone . . . and thus informing him in an authoritative manner of what he is and what he must be (p. 121, italics in original).

‘Become what you are’: that is the principle behind the performative magic of all acts of institution . . . . That is also the function of all magical boundaries (whether the boundary between masculine and feminine, or between those selected and those rejected by the educational system): to stop those who are inside, on the right side of the line, from leaving, demeaning or down-grading themselves. This is also one of the functions of the act of institution: to discourage permanently any attempt to cross the line, to transgress, desert, or quit (p. 122, italics in original).

Music education students enter universities from diverse backgrounds that include musical experiences in “subaltern” musical practices (rock bands, music theatre, hip hop, and other genres). After four years or so in the institutional environment, we send them out to the world somehow convinced that what they ought to be teaching is the Western canon. We generally accomplish this without directives and without conversations about the reproduction of cultural norms within the university experience. Programs hold up one model as the exemplar for inclusion in elementary and high school curricula. Students graduate and enter the teaching profession able to talk about or teach little else. Once in their own classrooms, the curricula they implement create two groups of students: those who buy into the cultural norms implicit in their curriculum, and those who opt out of school music. Those who disengage from school music often fail to see themselves as musical or musically “literate” (Joyce 2003), believing that musicality is a label that applies onto those with specialized training in institutionally-sanctioned forms of music making. The students who subsequently enter university music education programs (those in whom university music programs are primarily interested and actively recruit) are those who believe themselves to be musically literate—defined narrowly—thus perpetuating institutional whiteness. Gilroy (1993) suggests that such issues are

tied both to the fate of the intellectual as a discrete, authoritative caste and to the future of the universities in which so many of its learned protagonists have acquired secure perches . . . . The meaning of being an intellectual in settings that have denied access to literacy and encouraged other forms of communication in its place is a recurring question . . . (p.43).

If popular and world musics continue to be “other” forms of communication existing only outside of music education, the discipline perpetuates a system privileging the Western canon. University music programs thus deny access to “literacy” for vast numbers of students (those who never learned to speak the “language” of Western art music), while they also deny students who “speak canon” opportunities to learn to communicate effectively within musical forms that may better serve their future students. Even where university music education programs attempt to include meaningful experiences from diverse musical cultures, institutionalized whiteness often skews those experiences to reiterations of colonialism that rely upon what Said (1978) describes as a continual interchange between scholarly and imaginative constructions of ideas about the Other. These scholarly constructions (ethnomusicology as one example) are supported by institutions which make “statements about it [the Orient]), authorizing views of it, describing it, teaching about it, settling it, rulting over it” (p. 3). Graduates of such programs may enter the classroom with broader knowledge about a greater number of musical practices, but their understanding, developed through and framed by colonialist representations, often remains constrained by racialized binaries: Western music and “other” music; “our” music and “their” music; “high art music” and “popular” music, and so on.

Overcoming Color-Muteness in Music Education

What kinds of acknowledgements do we need to make, and what kinds of conversations do we need to have in order to disrupt the systemic racism embedded within music education? What might we do beyond pointing a discursive “fickle finger of whiteness” at the marching band as a performative reiteration of American capitalism, identifying contrived musical arrangements such as “Four Seasons of Haiku” as a form of cultural looting that reiterates colonial power relationships (Allsup 2005), or even theorizing an emerging multicultural human subjectivity (Bradley 2006a) as a potential outcome of anti-racism pedagogy within glocalized (Robertson 1992) communities? Such scholarship contributes to our understandings in important ways, but I want to move these and similar discussions, discussions in which race is an absent presence (Morrison 1992), from their institutionally white spaces to places where direct and meaningful conversations about race and racism take place.

Pollock’s (2004) research sought to understand why teachers and school administrators had difficulty talking about race. Originally framed as an ethnography in the “under-resourced, ‘low-income’ minority” (p. 2) population of a California school, Pollock soon realized that race played as great a role, if not greater, in the school’s difficulties as income or class. Yet, no one seemed willing to speak in racial terms, and indeed, were prohibited from doing so under California’s Proposition 209, which in effect outlawed any mention of racial categories in official documents. As she explains, “colorblindness can often be more accurately described as a purposeful silencing of race words themselves” (p. 3). Our socialization (as whites) causes us to become embarrassed, defensive, angry, or silent when conversation turns to race, and sometimes those responses occur even with the use of codes when they implicate whiteness as ideology (Solomon, Portelli, & Daniel 2005). But as Pollock’s study indicates, being color-mute actually makes race matter more; it perpetuates racial disparities while it simultaneously and systematically silences the language needed for description, analysis, and criticism. Since Proposition 209 effectively outlawed affirmative action in admissions to public institutions, “the representation of blacks and Hispanics at the two flagship universities declined precipitously” (Karabel 1999, cited in Karen 2007, p. 263). In San Francisco public schools, efforts to increase diversity through the criterion of family income (without reference to race), which officials originally hoped would simultaneously increase racial diversity, have resulted in the opposite: the number of schools where a single ethnic or racial group comprises 60 percent or more of the school population has increased sharply, from 30 to 50 schools, since 2001 (Glater & Finder 2007). Talking as if race does not matter has little effect on solving racial problems (Pollock 2004, p. 2).

How color-mute is music education’s discourse? We talk about musical culture, ethnic music, multicultural music, world music. Music is organized in textbooks by region, continent, nation, or by linear time periods that have meaning only within the context of European history. When we identify music from “Africa,” how big is the eraser we use to collapse 53 countries, hundreds of languages, and vast racial and ethnic diversity into one term? We sing South African freedom songs without ever speaking of the apartheid system that underscores their meaning; we sing spirituals and field yells from the southern U.S. without reference to human slavery; we largely ignore the music of North American indigenous peoples, thereby reiterating apartheid’s “out of sight, out of mind” mentality. We lament that our schools’ large ensemble participants are predominantly white, but do little to try to understand why. As hooks (2003) notes,

It has been easier . . . to accept a critical written discourse about racism that is usually read only by those who have some degree of educational privilege than it is for us to create constructive ways to talk about white supremacy and racism, to find constructive actions that go beyond talk (p. 29).

hooks and Pollock are right: We need to address our fear of talking about race, to find ways to bring race into our conversation as well as our written discourse so that we can move beyond talk to constructive action. In Colormute, Pollock (2004) makes specific suggestions for addressing the fear of talking about race: “In all conversations about race, I think, educators should be prepared to do three things: ask provocative questions, navigate predictable debates, and talk more about talking” (p. 221, italics in original).

While the number of recent articles and conferences suggest that music educators are beginning to ask provocative questions related to issues of social justice, including issues of equity, many academics and teachers still struggle personally at navigating conversational debates. Because white people have been socialized not to talk about race, we should anticipate the potential conflicts that may arise when we attempt to do so (Fishman & McCarthy 2005; hooks 2003; Pollock 2004; Rich & Cargile 2004). If we are not prepared for this to happen, promising conversations may quickly disintegrate into counter-productive arguments (Fishman & McCarthy 2005). Thus, as Pollock suggests, we need to be ready to navigate predictable debates and engage with them compassionately.

It is possible to overcome the reticence to talk about race if we continue to talk more about talking about race (Pollock 2004, p. 225). Talking self-consciously about race talk and its dilemmas permits us to acknowledge that we all face difficulties in talking about race, and that we will all make mistakes from time to time. As hooks (2003) notes, the emphasis on safety in feminist settings may at times work at cross purposes with our ability to talk meaningfully about race. She writes that in the process of unlearning racism,

one of the principles we strive to embody is the value of risk, honoring the fact that we may learn and grow in circumstances where we do not feel safe, that the presence of conflict is not necessarily negative but rather its meaning is determined by how we cope with that conflict (p. 64).

My hope is that we learn to take the kinds of risks that allow for productive conflict, so that we can begin to talk more about talking about race. In doing so, we may all move a little closer to the “color-blind future” that Williams (1997) sees, a day when race truly “doesn’t matter” any longer. This means that we must again look seriously at curriculum, rethinking “whose music” our curriculum valorizes and whose music is ignored, or even denigrated, from the viewpoint of the racial identities in question. As Ellsworth argues, as long as educators do not step outside of their field to point out the contradiction of institutionalized whiteness, it is likely we will remain paralyzed by the failure “to question the racialized paradoxes produced by certain academic practices” (Ellsworth 1997, p. 264). Ellsworth maintains that it is crucial to antiracist scholarship to “metacommunicate about how academic discourses and writing are themselves structured by racial relations” (p. 264).

For music educators, this suggests that we acknowledge and address the ways curricula (at all levels), research practices, audition requirements, and the musical skills that are most valued (to name a few key areas) are also structured by racial relations. We need to learn to talk directly about the raciology at work within music education. Towards this end, I conclude this paper with examples from my own teaching praxis in two separate settings that suggest how bringing race into our pedagogical efforts may encourage transformative learning. I offer these, not as prescriptions or quick fixes that will work in all settings, but as beginning steps towards overcoming color-muteness in music education.

The first example comes from my work with the Mississauga Festival Youth Choir inCanada. I have written elsewhere (Bradley 2006a, 2006b) about the deep sense of recognition that choir members experienced when they sang the South African freedom song, “Haleluya! Pelo Tsa Rona” before an international audience. The South African delegates at the Prison Fellowship International convocation, many of whom had been political prisoners under apartheid, jumped up spontaneously to sing and dance along with us. Interviews with my students long after the event suggest that one of the things the students took away from the “Haleluya! Pelo Tsa Rona” moment was a keener understanding of what the fight against apartheid in South Africa meant for those involved in that struggle. I believe this has much to do with the fact that in our rehearsals leading up to the concert, we talked about apartheid as a form of legalized racism. Our discussions about apartheid developed a context that supported learning the music and ultimately informed the choir’s performance of the song. My students were able, from these discussions, to make their own connections to other examples of racism in society today. We did not shy away from talking about race and racism, nor did we frame racism as something “in the past.” What I discovered in my work with these adolescents is that students are painfully aware of racism in their daily lives. For example, when the choir learned “Make Them Hear You” from the musical Ragtime, their comments revealed that they used the song as a lens for viewing the society in which they live. While interviewing choir members during my doctoral research, I asked each student if any of the choir’s repertoire was especially meaningful for them. Alicia,11 a fourteen-year old black woman, suggested the following:

Alicia: Well, I just think “Make Them Hear You,” because it is something that I can relate to. I guess because there’s still a lot of hate around, like the thing with Iraq and stuff, so even though that’s not exactly about racism, it’s still—it just kind of talks about the same thing (Interview, March 28, 2004).

Amber, a fifteen-year old white student, also volunteered “Make Them Hear You” as a song that helped her see injustice in the world around her:

A: Make Them Hear You is my all-time favorite, hands down. I like musicals and I love that song. And I—every time I hear the lyrics it makes me want to cry.

DB: Okay, can you talk about that a little bit? What is it about that song; what is in the lyrics that makes

A: I think the whole thing, just—like, “how justice was demanded and how justice was denied”—it makes me—I just think of all the people whose lives were affected by things like racism. And not like even just racism, but negativity towards other human beings for something they can’t help. I was talking about this with my mom in the car on the way here, actually. On the bus today there was this, I think, autistic kid on the bus, and after he got off there were these two guys I know rocking back and forth making fun of him, and I told them off. I’ve been in a bad mood for the rest of the day because it really bothered me (Interview, March 29, 2004).